Symptoms

Early symptoms include “stippling”—small necrotic (browned-out dead) spots on the tops of leaves; parched yellowing leaves that droop, turn brown, and fall off; spider-like webs, egg casings, and little black balls of fecal matter on the undersides of leaves, sometimes starting with the lower leaves and working up.

The little suckers are not insects, but arachnids, the same class of animals, Arachnida, as spiders and ticks. The reason they are called spider mites is that they string silken webs they use as highways. Two species of mites are most likely to annoy cannabis growers: the two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae), named for the two spots clearly seen on adults’ backs at maturity, and the Carmine spider mite or red mite (Tetranychus cinnabarinus). They are distinguishable from each other, but are usually grouped together as red mites because both species turn red in the fall as they prepare for diapause (hibernation) in temperate climates. Indoor growers rarely see them turn color, even when light hours are restricted during flowering. The warm temperature in the room keeps them active with no seasonal interruption.

There are several reasons why gardeners consider mites insidious. First, they are not apparent in the garden until they have already inflicted serious damage. Secondly, they are very small so they are likely to go unnoticed for some time unless you inspect the plants regularly. Third, they multiply so quickly that missing one can spell a new crisis in a few weeks.

Many garden book authors claim that once a garden is mite infested it is impossible to get rid of them. Then they recommend ways to “control” the plant killers. Mite predators can work to keep spider mite numbers to a minimum, but there is no way to really negotiate peace with these critters. They must be annihilated or they will succeed using the same strategy that insurgents practice: by conducting a war of attrition.

In this scenario, you, the garden, and the plants are “the establishment”. In order for you to win—that is, to maintain healthy plants that yield a large crop of healthful desirable buds—you must keep mites, “the insurgents”, at the most minimum of levels. Mites, on the other hand, don’t have to win to ruin your garden and cause the collapse of your little empire. They just have to not lose. So even if you are “winning” the battle and the mites are making little headway, they still affect the plants negatively. Under the control paradigm, there is constant war and you must be vigilant. The mites have the discipline to eat and reproduce. Do you have the discipline to plan a strategy and to carry it out? It’s a toss-up as to who will win.

Identification

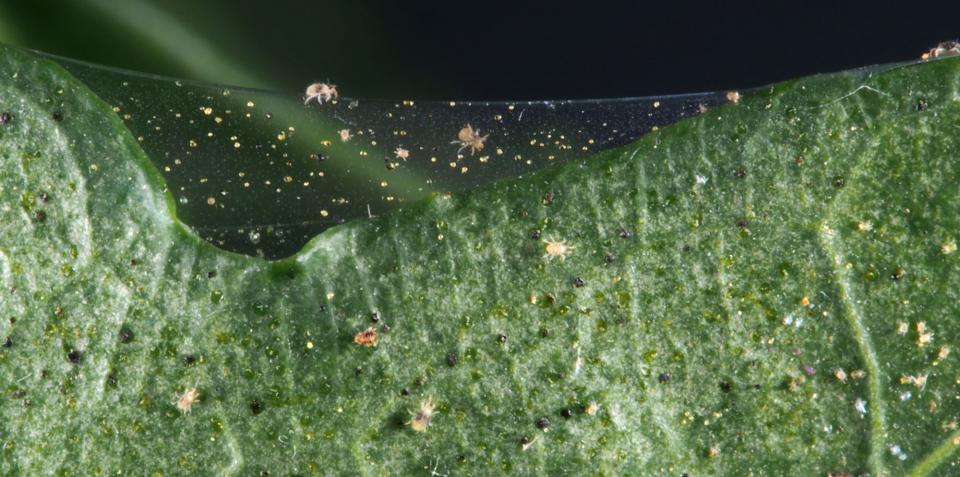

To the naked eye, mites appear as black dots on leaf undersides. They can be positively identified using magnification such a magnifying glass or photographer’s loupe. Mites are tiny and are more closely related to spiders and ticks than insects. They can be hard to see with the naked eye and harder to detect when the infestation is small. They have eight legs, no antennae, and a single, oval body region like their cousins the ticks. Their feeding structures are two needle-like feeding tubes called stylets with which they pierce plant tissue and suck out the plant juices.

Spider mites are most likely brought into greenhouses and grow rooms inadvertently, transported by gardeners or their pets, or on clones from infested mother plants. Damage from an early infestation is hard to spot. Mites puncture the plants to feed and leave behind tiny, light tan-colored spots on leaves called stippling. The tiny spot is visible from both sides of the leaf. It begins about the size of a pin-prick and then enlarges. Mites sometimes feed in lines parallel to the leaf veins where the juices accumulate.

An infestation quickly reaches epic proportions because of their fast maturation and high birthrate. You know you’re in trouble when leaves turn yellow then brown, droop, and fall off. The webs, which are highways between the leaves, are visibly apparent. The mites infest lower leaves first and they work their way up to the tasty, tender growth. Infestations are spotty at first, making the infection hard to detect. Symptoms quickly worsen. Left unchecked, whole plants eventually dry up from the juice sucking. The webs form scaffolding of silvery threads over the entire canopy.

Famed entomologist John McPartland developed a table of Infestation Severity for Mites. The time it takes a population to move from a light infestation to critical levels is just a matter of a few weeks:

Controls

Spider mites can be eliminated and it doesn’t take rocket science to do it. There are various high-tech environmental and chemical weapons as well as biological insect mercenaries that can be brought to the battle against mites. The first step is to assess your risk of mite infestation.

Garden location is the first determining factor. Warm areas surrounded by vegetation are at a higher risk for infection. Cool areas with salt air possess built-in deterrence. I know several gardeners who maintain indoor gardens within eyeshot of the ocean. The salt-air breezes keep pests, especially mites, from the local vegetation so there is less of a chance of infestation.

The second risk factor for indoor gardens are the points of entry. Since mites don’t generate spontaneously, there must be a source of infestation. How were they introduced? Most likely a human or pet carried a mite in or a new plant introduced it to the garden. The ventilation system is another likely culprit. Unfiltered air intake offers no protection against mites. If this source of infestation is continuing, stop it. It doesn’t pay to eliminate pests only to have them re-infect. Use a HEPA filter or an insect/mite shield filter over the air intake tubing.

You cannot successfully treat just one section of a garden for mites. The entire garden must be treated at the same time because you will not be able to keep the pests from re-infesting the cleaned part of the garden if there are areas that are still contaminated. This is obvious if the garden is in a single room. However, several grow areas in the same structure or even in separate structures may constitute one garden because of the traffic between them.

Poor sanitation is a related, but third source of risk. It is important to follow the guidelines for preventive maintenance. Keep plant debris swept up or picked up to eliminate areas where mites live. If possible, keep a 10-foot weed-free zone around grow rooms or greenhouses as they are hosts for mites.

Rigorous garden-entry protocols greatly reduce the chance of mite infestation, but they are similar to using birth control—one slip-up and all your efforts can be rendered moot. However, that kind of one-shot luck is rare. Suffice it to say that these policies rely on vigilance to work. Never go from an infected to a non-infected garden without bathing and changing your clothes. If you don’t plan on washing your hair place a protective hat or shower cap over it in both gardens.

New plants are not exempt from entry protocols. Dip all new plants in a miticide. Then quarantine them for 10 days until they are cleared of suspicion. These policies are a particularly good practice for mites and other plant pests and they improve overall health and pest prevention in the garden. Take care not to introduce mites from mother plants into growing room.

If mites are discovered in the garden, keep their fast-paced life cycle in mind and don’t procrastinate. Begin treatments ASAP. Here are some effective methods of treatment to implement.

Physical Removal

Power washing and vacuuming reduce the population and immediately reduce stress on the plants, but are only a first step in a multi-pronged approach to mite control. These two methods are simple, don’t introduce any chemicals or substances to the garden, and bide time before introducing other measures.

Pesticides often referred to as miticides

Herbal Pesticides – several herbs and spices are effective when used as deterrents:

· Capsaicin, the heat of hot pepper plants, deters spider mites. However the treated leaves cannot be processed to make edibles but can be used for other preparations.

· Herbal oils such as cinnamon, clove, coriander, lemon grass, geranium, rosemary, sesame, garlic, and oregano, or herbal oil mixtures, are extremely effective. You can make your own with a single ingredient or a combination of ingredients. There are a number of commercially produced herbal-based miticides including Ed Rosenthal’s Zero Tolerance and SNS-217 Spider Mite Control.

· Brewed tea: Rather than using spice oils, you can brew a spice tea by steeping spices or herbs in hot water. Citrus rind contains D-limonene, which is also a very effective miticide. It can be added to the brew. Citrus oil miticides are available commercially.

· Some light horticultural oils can be applied as a “summer” spray, but only during vegetative stage.

· Neem oil, pressed from the seed of the neem tree, is an effective miticide.

Insecticidal soap knocks down populations but is a temporary stopgap because it must be used repeatedly, building up layers on the leaves. It reduces rather than eliminates the problem.

Pyrethrum is only effective against some mite populations. Because of its extensive use in agriculture, most populations have developed immunity to it.

Sulfur burners are effective at eliminating mites. Only some eggs are killed so the burn must be repeated after several days.

Biological Controls

Biological controls can play a key role in eliminating mites. They are effective because they are able to reach all of the suckers.

· Bacteria: Saccharopolyspora spinosa (Spinosad) This naturally occurring soil bacterium is useful against ants, spider mites, caterpillars, and leaf miners, but must be ingested to work and is toxic to bees.

· Fungus: Beauveria bassiana This fungus also works against aphids and whiteflies, but it cannot be used in conjunction with beneficials.

· Insects and beneficial mites insects do not eliminate mites from the garden. Under the best circumstances they bring the population down so low that there is effectively no damage to the plants.

· Bugs: Minute pirate bugs (Orius spp.) These guys love to eat spider mites. Introduce 50 adults for every 100 square feet of space.

· Midges, Gall: Feltiella acarisuga (Cecidomyiid gall midge) Midges are small fly-like insects. F. acarisuga spend their lives seeking spider mites to eat, making them a great choice. This is an excellent insect choice in vegetative gardens. They must be introduced when mite populations are low or reduced.

Predatory Mites

Many predatory mites specialize in two-spotted mites. While they can be introduced in high concentrations to control a heavy infestation, they are best to use when populations are low. Introduce them after reducing the population using physical treatments or herbal pesticides. The key is matching the predators with your specific environment. Each species has its own temperature, relative humidity, and light needs that must be considered for successful results.

· Amblyseius californicus (sometimes identified as Neoseiulus californicus)

· Galendromus occidentalis: western predatory mite, most tolerant and versatile predator mite

· Mesoseiulus longipes: although not the most voracious predator, it is tenacious and is more flexible on conditions than many predatory mites.

· Neoseiulus fallacis, also known as Amblyseius fallacis: good candidate for grow rooms and greenhouses, these mites are tolerant of a wide temperature range 75 to 90 degrees F (23 to 32 degrees C).

· Phytoseiid mites (Phytoseiulus persimilis): a voracious eater of spider mites, but only works in high humidity environments.

On a personal note, I have never had much success with beneficial mites. When I have seen them used successfully they were constantly reintroduced. They were not self-sustaining.

Français

Français